The Real History behind I've Known Rivers

Read about York's experience growing up on the Kentucky frontier and on the expedition

York was born in Caroline County near Chesapeake Bay Virginia in 1770, the son of an enslaved woman and Old York, an enslaved Black man. Eager for the promised riches of Kentucky, John and Anne Clark sold their farm and floated down the Ohio River to the wilderness settlement of Louisville in 1785. The Clarks uprooted their own family and the enslaved families they brought with them, including York and his father. When John Clark died, William inherited and owned York. In 1803, William Clark brought York on the Lewis and Clark Expedition. York was the first enslaved man to march from coast to coast in North America.

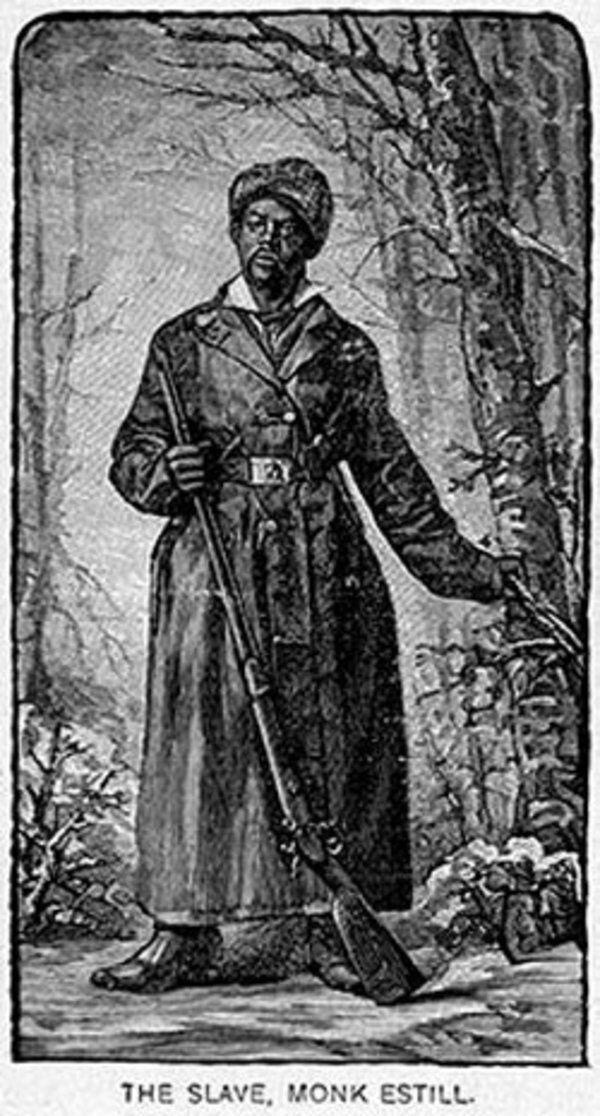

"Larger than life he was. Caesar who held a musket, two blades, wore mocccasins and marched a thousand miles. Now there was a Negro of the frontier, like Monk Estill and Burrell. The tales he told when I first came to Kentucky, how he fought side by side with Mister George when he was the general who won all those battles up in the Ohio territory. Caesar spied on on the Shawnee, the Wea, on all the redmen who sided with the redcoats in the war against the crown. He was true to his name but Mister George wore him out with poor rations and battle wounds. He perished and never breathed a single day as a freed man."

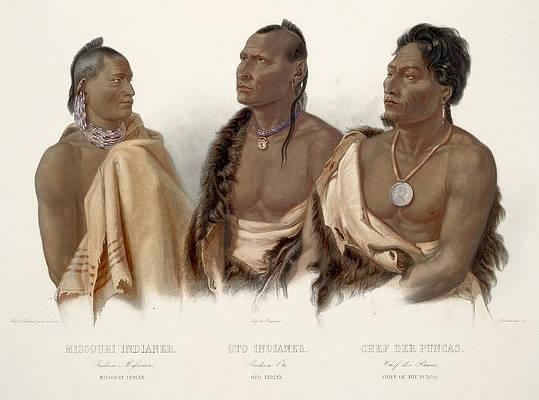

"One of the men has black hair so curly there’s surely a Negro somewhere in his family tree. He has deep creases on his face and has the serious, all discipline expression of Sergeant Ordway, only he’s trying to get the Missouri to obey his commands. He never leaves the bow and peers down at the surface as if he were reading a map."

"The captain and Mister Billie turn to Drouillard, who’s listening to the Otos. The grandfather from the day before has wet cheeks. An old man from the warrior tribe, one that fed its enemies arsenic stew, is wiping his eyes, weeping.

“He say when their petit enfants steal, very bad. Lies, bad, mais, they no whip them,” Drouillard says.

“Tell him he walked the war path against his chief and for that he is punished,” Captain Lewis says.

The captain and Mister Billie turn to Drouillard, who’s listening to the Otos. The grandfather from the day before has wet cheeks. An old man from the warrior tribe, one that fed its enemies arsenic stew, is wiping his eyes, weeping.

“He say when their petit enfants steal, very bad. Lies, bad, mais, they no whip them,” Drouillard says."

The Teton crowding the river bank make no move to come out to the keel, but it is like before. More and more of them stream out. The squaws in their buffalo robes with their shiny black hair, file out last. They do not wail out their incantations, they just stand there. They are casting another spell upon us.

A tall brave with a shaved head and a knot sprouting out of the top of his skull swims out to the rope and grabs hold of the keel boat’s anchor rope.

Each side drawn, waiting, and ready to fire. Hundreds of them against us.

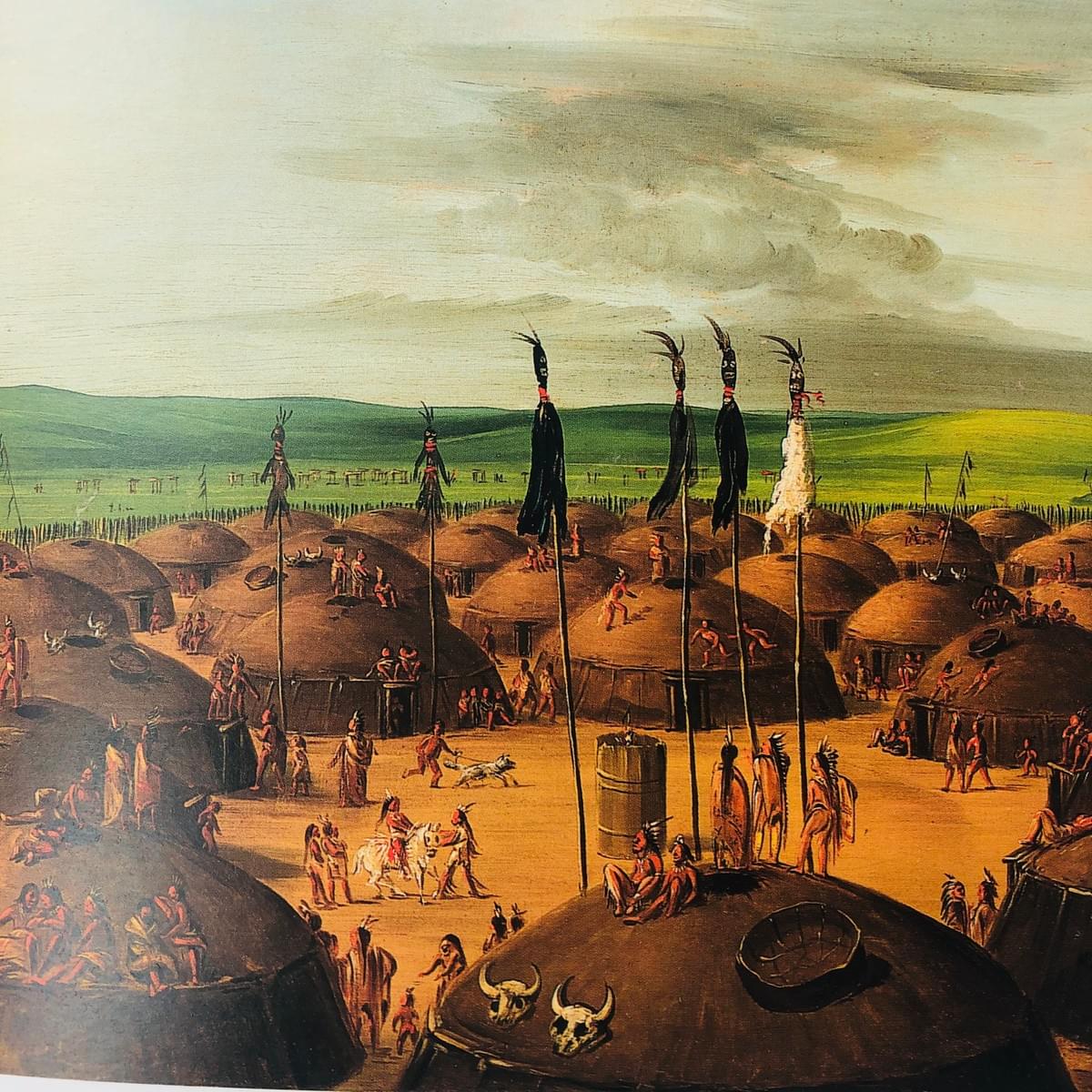

“Would you look at that,” I say, stunned as the natives walk out from their anthills.

“Yes. Remarkable. They dwell within the earth itself,” Mister Billie answers.

Children and warriors sunning themselves atop the mounds wave in greeting. In minutes, throngs of them surround us. Drouillard and Sergeant Pryor disappear into a sea of raven colored heads. Walking through the lanes of their village, each house is a completely round molehill some forty feet across with smoke drifting out of the top of them.

“Would you look at that,” I say, stunned as the natives walk out from their anthills.

“Yes. Remarkable. They dwell within the earth itself,” Mister Billie answers.

The maiden recognizes Sacagawea because the Minetarris caught her too, on the same day, only she jumped off their horse. They gave her up for drowned and she limped miles back to the Snakes. She rubs Jean-Baptiste’s head and calls over to a man with the decorated hair, calling him Cam-a-wait. Sacagawea looks up at him, says not a word and throws one of Jean-Baptiste’s swaddling blankets up over his head. Then she pulls it off, the chief speaks and the girl who escaped the raid weeps. Saca stares at the Snake brave. He is older than she is, with sun darkened skin, creases about his eyes, a sharp chin and a mane of hair woven up with shells.

“Quelle?” I ask Charbonneau. “Who is it?”

“Son frere.”

Her brother.

The farther he paddled into the wilderness, the more freedom he had. On the 1500 mile journey up the Missouri River, York had a gun, hunted, and swam, which he could not do in Kentucky of 1804. Struggling against the waves and whirlpools in the Missouri, fending off a battle with the Sioux, marching on through the snowstorms of the Rockies, York was the first enslaved Black man riding down the Columbia River to the Pacific Ocean. Replace photo of Black woman with Sold to the South Text When the expedition returned, the officers were hailed as heroes, and York returned to a slave society and was forced to live again as William Clark’s enslaved servant. When Clark became the superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Missouri Territory, York did not remain in St. Louis. In letters to his brother, Clark complained of York’s obsession with visiting his wife back in Kentucky and threatened to sell him. York’s love of his family is why York did not escape to the wilderness to live out his days among Natives. In his last interview a few months before he died, William Clark told writer Washington Irving that he freed York. There is little evidence to support this. What Clark did do is hire York out for a year to another master. Landon Y. Jones in his history of William Clark, says there is no record of a single Clark among the ten siblings of ever freeing their enslaved property. The Clarks, Jones writes, kept their slaves.

© 2022